Casualisation has been a central feature of the erosion of UK higher education over the last twenty years. It has paralleled and made possible most of the worst aspects of marketisation within the university sector. In the HE Pay and Equality Ballot 2018/19, we are voting on whether or not we want to contest the normalisation of precarious and insecure working conditions for our colleagues, the impact of which can be viewed in testimonies supplied by our colleagues:

“After paying my rent and the bills, I have around £250 to live on per month. I have had to take a number of part-time jobs over the years in order to sustain myself financially, including paying my £2000/year PhD tuition fees. This has an important impact on my PhD writing as I am often unable to dedicate enough time to it – this being another source of great anxiety.”

“My job prospects don’t look good. As this is my third year of teaching the department will most likely not offer me a fourth contract as this is technically not allowed. I’m preparing myself for even more precarious casualised working and living conditions after I finish my PhD and consider resorting to my old job in order to be able to pay the bills.”

“Even after three years of teaching it takes me at least twice the amount of time than allocated to be able to properly mark essays. It is impossible for me to read a 3000 word essay, make notes, write feedback, fill in the report and upload it on the VLE within 35 minutes.”

“Recently I was unable to put my name on my tenancy contract due to my financial insecurity. The agency said that a student grant is not a “certain income” and that as a result I do not count as the “employed professional” they require.”

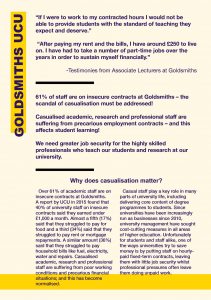

“If I were to work to my contracted hours I would not be able to provide students with the standard of teaching they expect and deserve.”

“There was no training, guidance or support given or even offered to me in preparing my classes. Nevertheless, and perhaps because of that, I worked very hard to prepare my one weekly seminar. I spent at least 8 hours, if not more in the first weeks, doing the required readings plus extra in order to be knowledgeable in the course content. Who wants to stand in front of a group of students not being sure about the week’s topic? I went to all the lectures even though I did not get paid for my time to do so, nor for the vast majority of my time preparing the seminars I was responsible for. It’s grossly unrewarding and frustrating, working so hard and knowing that most of it is for free.“

University management has systematically undermined the security of permanent employment for academics, professional and research staff, which it sees as too costly or risky. By increasing the use of insecure and provisional contracts they have offloaded the risk of a fluctuating market onto a reserve army of casual staff. This matters because staff on insecure contracts struggle to deliver the high level professional service expected of them in the face of working conditions that leave them underpaid, vulnerable and constantly facing the prospect of unemployment.

Casual staff make up a growing part of the university workforce and they play a key role in delivering core content of degree programmes. Yet, according to 2016/17 HESA data compiled by UCU, over 61% of staff are on insecure contracts at Goldsmiths. Ultimately, the costs of these tactics trickle down onto students, who receive their standardised just-in-time education by burned-out staff members, permanent staff who suffer from excessive workloads as well as the institutional consequences of dissatisfied students.

But casualisation is also a key mechanism used to support the fiction of resource scarcity in the sector. This has allowed a hyper-competitive climate within academic employment to flourish and has diminished workers’ capacities to fight back against ever worsening conditions. Casual staff working hourly paid contracts are almost always doing many hours of free work to do their jobs properly. For many, teaching is not simply a rite of passage in their academic career, but is one of their main sources of income and takes up a sizable part of their working week. The principle of “equal pay for equal work” is often not being enacted and current pay conditions do not reflect the reality of time-spent working as teachers. A report by UCU in 2015 found that 40% of university staff on insecure contracts said they earned under £1,000 a month. Almost a fifth (17%) said that they struggled to pay for food and a third (34%) said that they struggled to pay rent or mortgage repayments. A similar amount (36%) said that they struggled to pay household bills like fuel, electricity, water and repairs.

The excerpts of testimonies we’ve gathered from casual staff at Goldsmiths confirm all of the above in grim detail. None of these are exceptional cases but reflect a very common reality experienced by casualised academic staff. The Joint Higher Education Trade Union National Claim 2018/19 that has been submitted to the Universities and Colleges Employers Association (UCEA) to which the current ballot refers, makes substantial demands on the part of casualised staff. It stipulates that a vote in favour of the claim will establish a mandate to force the UCEA to commit to radically transforming employer orthodoxy with regard to casual contracts. This is a crucial opportunity for UCU members who benefitted from the militancy of their junior colleagues during the USS strikes to show solidarity to a campaign that will drastically improve the working conditions of precarious workers, a struggle which will undoubtedly enhance the working lives of all academic staff.

This week we are asking all members to show solidarity with our casualised colleagues, by sharing the publicity about conditions at Goldsmiths/across the sector – and by casting your vote in the pay an equality ballot.

A meeting to discuss anti-casualisation at Goldsmiths will take place on Weds 23 January, 12noon, MMB212.